1. Introduction & Definition

The term “emo” has been twisted, rejected, mocked, embraced, and redefined countless times over the past four decades (emo is 40 years old this year!).

Originally short for emotional hardcore, it began as a small, introspective offshoot of the 1980s hardcore punk scene. In its earliest days, emo was about raw emotional honesty in a genre that had built itself on political anger and aggression.

Over the years, the term and idea of “emo” expanded far beyond its underground roots. It is, above all else, a sprawling cultural phenomenon. By the 2000s, it was both a music genre and a full-fledged youth subculture; one that encompassed fashion, online communities, and a distinct social identity. This transformation caused confusion: was emo a style of music? A fashion statement? A personality type? The answer depends on when.

Today, the word emo often conjures images of mid-2000s mall culture: black skinny jeans, band tees, eyeliner, and lyrics about heartbreak. But emo has had a complex evolution. Its history reveals different sounds, aesthetics, and philosophies with each distinctive wave.

2. Origins (Mid-1980s) — Emotional Hardcore

Emo’s roots trace back to Washington, D.C., during a period of burnout in the hardcore scene. By the mid-1980s, many bands and fans were disillusioned with hardcore’s growing emphasis on aggression, violence, and uniformity. Hardcore's original spirit of individuality and resistance had been diluted, leaving it feeling codified and inauthentic. As seems to always be the case in music, this type of exhaustion made space for something new to form.

Out of this decline emerged a movement called, Revolution Summer (1985), which sought to create a more inclusive and personal form of punk rock. Dischord Records, the label founded by Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, Embrace, and Fugazi, became the axis for the new sound and ethos.

Bands like Rites of Spring and Embrace set the tone for what was to come through their performances, music, and lyricism. Their shows were intimate and intense, often taking place at DIY venues and people's homes. They slowed the pace of hardcore and infused it with vulnerability and melodic experimentation, and the lyricism became more internal and introspective rather than political.

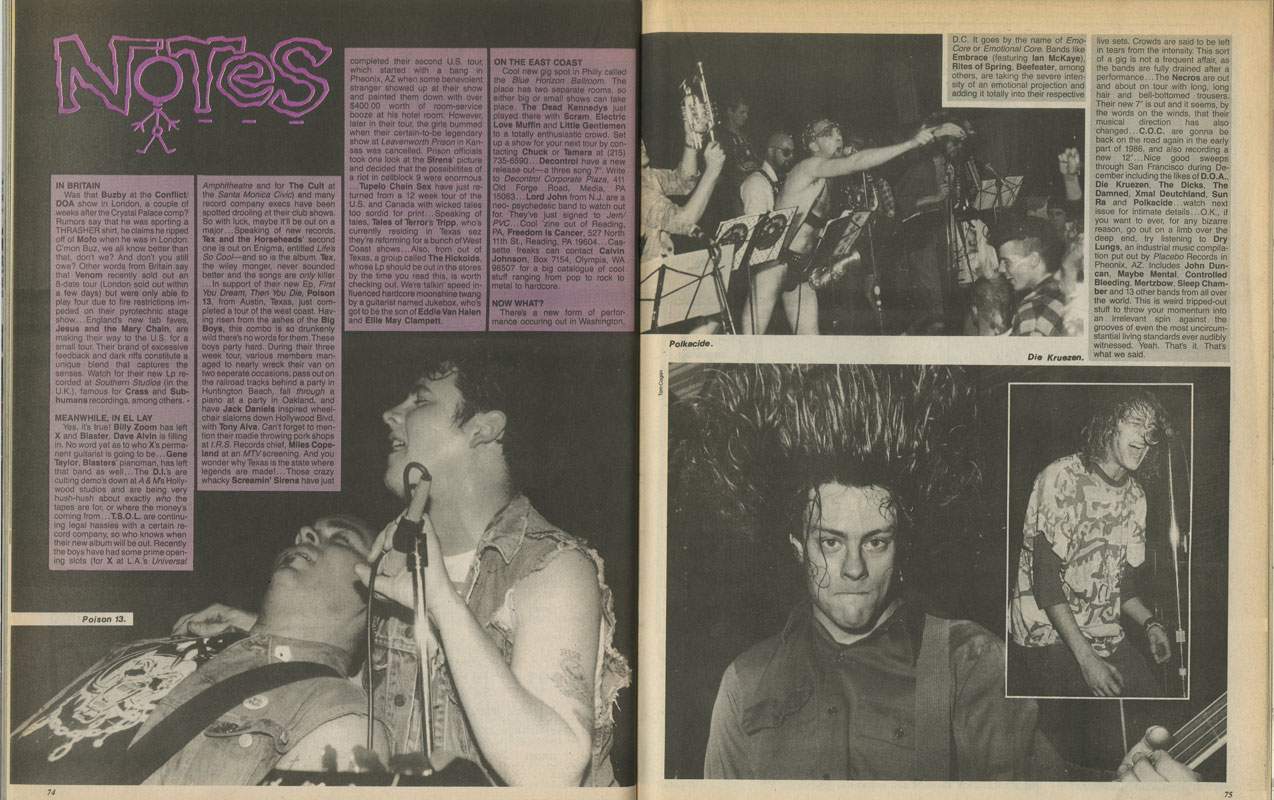

From these new ideas the term "emo" was born. The first known written use of the term was in January 1986 by Thrasher Magazine. They used it to describe a new sound out of the Washington, D.C. hardcore punk scene, describing it as "Emo-Core" or "Emotional Hardcore." Although this first "emo" wave was geographically contained, it set the mold for every future iteration of the genre.

3. First Wave (Late 1980s–Early 1990s)

The sound didn’t stay locked in D.C. for long. By the late ’80s, emotional hardcore began to branch out. In the Midwest, it blended with indie rock and post-hardcore. This shift is sometimes referred to as the first wave outside of D.C. (though some fans determine it as the second wave because they consider Revolution Summer the first.) Simultaneously, a harsher, more chaotic form was taking shape on the West Coast. This sound would later be known as screamo.

The key characteristics of the First Wave were varied, depending on the scene. In the Midwest, guitars were considered to have a “janglier” sound, tempos shifted more freely, and song structures were less rigid. Cracked voices and earnest yells were more important than perfect pitch because the point was emotional expression and pure feeling. The influences grew to encompass post-punk, indie rock, and even folk elements. Notable bands with the Midwest sound that defined these characteristics include Cap’n Jazz, Sunny Day Real Estate, and Jawbreaker. These bands and more all had unique approaches that strengthened and broadened emo.

Meanwhile in San Diego, bands on Gravity Records like Heroin, Swing Kids, and Antioch Arrow began intensifying the hardcore roots of emo into something noisier, faster, and more cathartic. This was the first wave of screamo, characterized by frantic tempos, screamed vocals, and frenzied breakdowns. Unlike the Midwest’s melodic melancholy, screamo aimed for channeling raw emotion in a more abrasive way.

Both movements shared a commitment to the DIY spirit. Shows remained small and intimate. The bands played in basements, community centers, and VFW halls, and the fan base was deeply rooted in underground zine culture and tape trading networks. Indie labels like Jade Tree and Polyvinyl were crucial to the indie-emo branch, while Gravity Records became synonymous with early screamo.

By the early ‘90s, emo was no longer some hardcore offshoot. It became its own eclectic community with many stylistic approaches. This widening of influences and sounds gave it a broader category of fans, and thus started the Midwest and Screamo explosion in the mid-’90s.

4. Second Wave (Mid-1990s)

By the 1990s, emo had branched into several distinct sounds. Where the First Wave laid the foundation with jangly guitar and chaotic melodies, the Second Wave expanded both of these threads. By the second wave, emo was set to be a permanent and ever evolving genre and movement.

Bands like American Football, Braid, and Mineral leaned into twinkly guitars and melancholic lyricism. They were part of the emo sound that makes one think of black-rimmed glasses, flannel, and sensitive college-aged kids packed into underground venues. Though this sound was niche, it would later inspire the emo-pop crossover of the 2000s.

Meanwhile, screamo grew in the West Coast and the East Coast. Bands like Orchid, Saetia, Jeromes Dream, and Pg. 99 were pillars of the screamo sound that would later influence the post-hardcore bands of the early 2000s, particularly Thursday, Glassjaw, and Thrice. They had screamed vocals, sudden tempo shifts, addictive, intense crescendos, and cathartic performances — a lot of the ideas of emo that we sit with today.

By the end of the ‘90s, “emo” described an umbrella of different sounds, including Midwest emo, screamo, and melodic hardcore (a blend that may have not dominated the scene, but did serve as connective tissue for the future blend of emo later down the line.)

5. Third Wave / Mainstream Breakthrough (Early–Mid 2000s)

The idea of “emo” that is the most familiar and popular to us now is the Third Wave from the early to mid 2000s, and this was the era in which emo emerged into the mainstream, specifically from the screamo and pop-punk/emo-pop movement. Bands like Underoath, Silverstein, and Thursday are what we think of when we picture the mall emo (skinny jeans, eyeliner, studded belts) because this was the look that meant they were most probably into screamo and post-hardcore.

This is the era when basements and house shows became Warped Tour lineups, MySpace feeds, and MTV countdowns.

The Midwest’s indie-leaning sound laid the foundation for the softer, more melodic side of the Third Wave. Bands like Jimmy Eat World and The Get Up Kids polished the emo sounds, opening space for broader audiences.And from this lineage came the emo sensation that completely defined the 2000s — the high we’re still chasing today. While bands like Taking Back Sunday and Fall Out Boy were flirting with a more emo-pop sound, a darker style of emo was also becoming popular. A genre that had leaned apolitical for the most part had now met its match with the band Thursday.

Thursday’s Full Collapse (2001) became the defining record of this transition. Geoff Ricky’s poetic and sometimes political lyricism, the screamed/melodic vocal mix, and explosive crescendos made Thursday the bridge between hardcore fury and emo emotionality. Thursday was renowned for their contributions to the emo sound from their own albums, but they were also leaving a mark on emo in a different way: Geoff Rickly was the producer of My Chemical Romance’s first album, I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love.

My Chemical Romance, whether believed to be “true emo” or not by the "Emo Police," were the most defining band of 2000’s emo culture. They deserve an entire journal of their own because their influence cannot be overstated. The music, the drama, and the look of the 2000s emo will hold My Chemical Romance in the epicenter for what seems like ages to come. While their first album was not their breakthrough album, it is highly revered among their fans today, making Thursday and My Chemical Romance pillars of the emo genre in their own right.

Alongside Thursday, bands like Thrice and Finch blended post-hardcore sensibilities with emo’s vulnerability, paving the way for Warped Tour’s heavier acts. And from here, the sound spread. Silverstein, Hawthorne Heights, and Senses Fail fused screaming intensity with melodic choruses. Screamo was no longer a niche — it was a headlining attraction on the same stages as Fall Out Boy and Paramore.

This Third Wave of emo was supercharged by a cultural famework that turned a genre into a lifestyle and identity. Exposure on top of exposure on top of exposure — Vans Warped Tour putting all kinds of emo and screamo acts in their tour which led to nonstop music discovery for concert-goers, MTV music video premieres showcasing iconic music videos like My Chemical Romance's “Helena,” the internet making it easier to connect and share your identity and favorites, and accessible band merch and other defining attire at Hot Topic. These elements turned emo from a music genre to an easily identifiable subculture. It was a place to belong — which garnered widespread attention from youth that already felt like they didn’t fit in or knew that they felt things differently.

Ironically, as emo became such a buzzword in marketing and media, many bands rejected it. This tension between emo identity and denial by famous acts meant the meaning of emo was contested, leading to its high appeal but also its eventual deceleration.

The Third Wave was emo’s mainstream peak: the moment in which it could no longer be ignored, even as its definition remained hotly debated. By the mid-2000s, emo had become a full-fledged subculture. It was visible in music, fashion, and online life. It was a shared experience, identity, and belonging for the suburban teen. There was no denying that emo was a cultural identity as much as a musical one. To this day, it is still a growing and evolving subculture with many loyal members and fans who define it even further.

(Note: a section on the 2010s “emo revival” and later developments will be added in a future update.)